AP Physics 1 Study Guide: A Comprehensive Plan

Embark on a focused journey! This guide utilizes the 2026 AP Physics 1 exam equation sheet‚ offering crucial formulas and constants for success.

Master key concepts with derived formulas‚ ensuring a solid grasp of kinematics‚ dynamics‚ and energy principles for a top score.

Utilize the AP Physics 1 formula sheet‚ a vital resource containing commonly used equations‚ to confidently tackle challenging problems.

Welcome to AP Physics 1! This algebra-based course emphasizes conceptual understanding and problem-solving skills. It’s a challenging‚ yet rewarding‚ introduction to the fundamental principles governing our physical world. Preparation is key‚ and utilizing resources like the official AP Physics 1 course description and the equation sheet is paramount.

This course covers a broad range of topics‚ including kinematics‚ dynamics‚ work‚ energy‚ momentum‚ rotation‚ and simple harmonic motion. Success hinges on mastering these concepts and applying them to real-world scenarios. Familiarize yourself with the constants and conversion factors provided in the AP Physics 1 Table of Information.

Effective study habits‚ consistent practice with MCQ tests‚ and a thorough understanding of the provided formulas will significantly enhance your performance. Remember‚ the equation sheet is a valuable tool‚ but knowing when and how to apply the equations is crucial for achieving a 5 on the AP exam.

II. Kinematics

Kinematics is the foundation of AP Physics 1‚ describing motion without considering its causes. Mastering this section requires a firm grasp of displacement‚ velocity‚ and acceleration – both linear and angular. Utilize the kinematic equations (with constant acceleration) extensively; they are essential for solving a wide range of problems.

Focus on understanding the relationships between these variables and how they change over time. Practice applying the equations to scenarios involving objects moving in one and two dimensions. Remember to pay close attention to sign conventions and units. The AP Physics 1 formula sheet provides these equations‚ but memorization isn’t enough.

Conceptual understanding is vital. Can you explain what each variable represents? Can you choose the correct equation for a given situation? These skills‚ combined with diligent practice‚ will set you up for success in this crucial kinematic section.

A. Displacement‚ Velocity‚ and Acceleration

Understanding displacement‚ velocity‚ and acceleration is paramount in AP Physics 1. Displacement is the change in position‚ a vector quantity. Velocity describes the rate of change of displacement‚ also a vector. Acceleration represents the rate of change of velocity;

Differentiate between average and instantaneous values for both velocity and acceleration. Recognize how these quantities are related graphically – the slope of a position-time graph is velocity‚ and the slope of a velocity-time graph is acceleration.

Mastering vector addition is crucial‚ as these quantities often act in multiple dimensions. Utilize the AP Physics 1 formula sheet for relevant equations‚ but prioritize conceptual understanding. Practice solving problems involving varying accelerations and initial conditions.

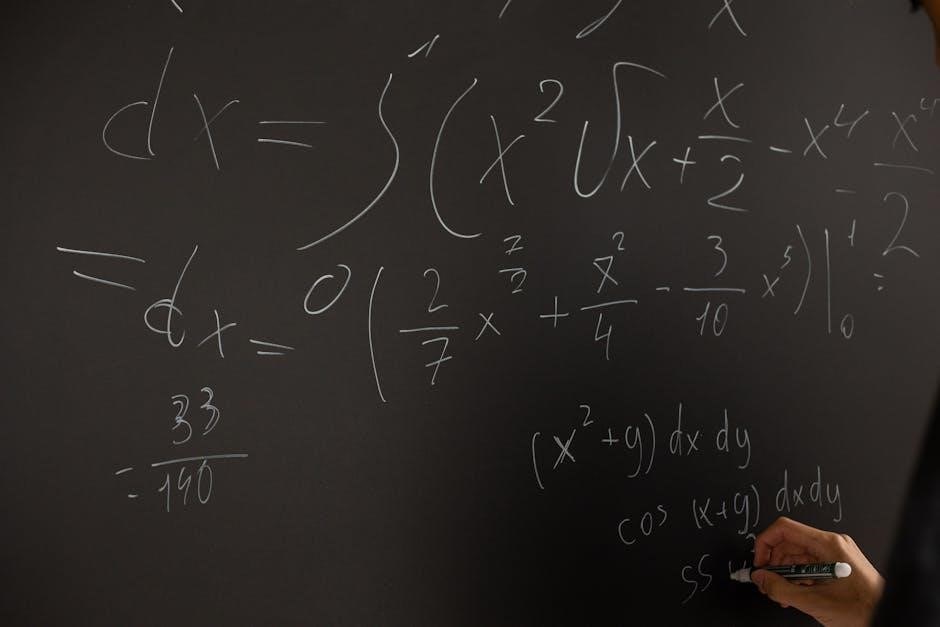

B. Kinematic Equations (Constant Acceleration)

Kinematic equations are fundamental for solving problems involving constant acceleration in AP Physics 1. These equations relate displacement (Δx)‚ initial velocity (v₀)‚ final velocity (v)‚ acceleration (a)‚ and time (t).

Memorize and understand the following: Δx = v₀t + ½at²‚ v = v₀ + at‚ and v² = v₀² + 2aΔx. Recognize when these equations are applicable – only when acceleration is constant.

Practice identifying the known and unknown variables in a problem‚ then strategically select the appropriate equation. The AP Physics 1 formula sheet provides these formulas‚ but efficient problem-solving requires fluency. Be mindful of units and vector directions!

III. Dynamics

Dynamics delves into the causes of motion‚ primarily through Newton’s Laws of Motion. Understanding these laws is crucial for AP Physics 1 success. The first law defines inertia‚ the second (F=ma) relates force‚ mass‚ and acceleration‚ and the third describes action-reaction pairs.

Mastering forces like gravity‚ friction‚ tension‚ and the normal force is essential. Learn to draw free-body diagrams to visualize all forces acting on an object.

Apply Newton’s Second Law to analyze motion in various scenarios. Remember to resolve forces into components when dealing with angled forces. The AP Physics 1 equation sheet provides the necessary formulas for force calculations.

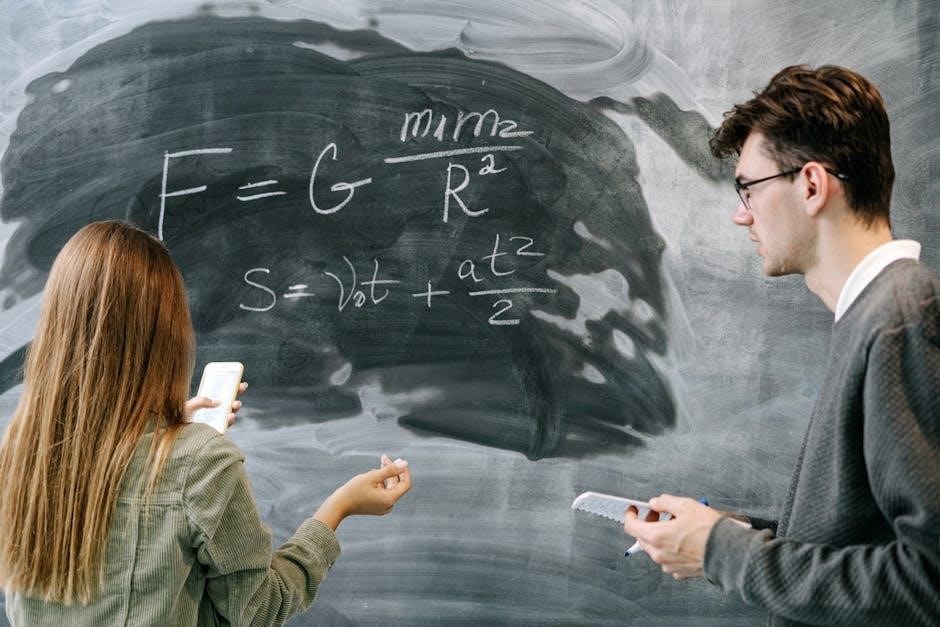

A. Newton’s Laws of Motion

Newton’s Laws of Motion form the bedrock of classical mechanics‚ essential for AP Physics 1. The First Law‚ inertia‚ states an object at rest stays at rest‚ and vice versa‚ unless acted upon by a net force.

The Second Law‚ F = ma‚ quantifies the relationship between force (F)‚ mass (m)‚ and acceleration (a). This is a cornerstone equation for problem-solving.

Finally‚ the Third Law dictates that for every action‚ there’s an equal and opposite reaction. Understanding these interactions is vital. The AP Physics 1 formula sheet doesn’t explicitly state the laws‚ but they underpin all dynamic calculations.

Practice applying these laws to various scenarios to build a strong conceptual foundation.

B. Forces: Gravity‚ Friction‚ Tension‚ Normal Force

Mastering fundamental forces is crucial for AP Physics 1. Gravitational force‚ Fg = mg‚ acts downwards‚ where ‘g’ is the acceleration due to gravity. Friction opposes motion‚ with static and kinetic friction having different coefficients.

Tension‚ exerted by ropes or cables‚ acts along their length. The Normal Force‚ a contact force‚ acts perpendicular to surfaces‚ preventing interpenetration. These forces often appear in combined scenarios.

The AP Physics 1 equation sheet provides the gravitational force constant‚ aiding calculations. Remember to draw free-body diagrams to visualize all forces acting on an object.

Practice resolving forces into components for accurate analysis and problem-solving.

IV. Work‚ Energy‚ and Power

Understanding work‚ energy‚ and power is central to AP Physics 1. Work done by a constant force is W = Fd cos θ‚ where θ is the angle between force and displacement.

Potential energy exists in two forms: gravitational Ug = mgh and spring Us = ½kx2. The conservation of energy principle states that total energy remains constant in a closed system.

Kinetic energy‚ KE = ½mv2‚ represents energy of motion. Power‚ the rate of doing work‚ is P = W/t. The AP Physics 1 formula sheet provides these essential equations.

Practice applying these concepts to solve problems involving energy transformations and efficiency.

A. Work Done by a Constant Force

Work‚ in physics‚ represents energy transfer when a force causes displacement. The fundamental equation for work done by a constant force is W = Fd cos θ‚ where F is the magnitude of the force‚ d is the magnitude of the displacement‚ and θ is the angle between the force and displacement vectors.

If the force and displacement are in the same direction‚ cos θ = 1‚ simplifying the equation to W = Fd. Understanding the angle is crucial; work can be positive‚ negative‚ or zero depending on θ.

The AP Physics 1 formula sheet provides this key equation. Mastering this concept is vital for understanding energy transfer and solving related problems.

B. Potential Energy (Gravitational & Spring)

Potential energy represents stored energy due to an object’s position or configuration. Gravitational potential energy (GPE) is calculated as Ug = mgh‚ where m is mass‚ g is the acceleration due to gravity‚ and h is the height above a reference point.

Spring potential energy‚ resulting from compression or extension‚ is given by Us = ½kx2‚ where k is the spring constant and x is the displacement from equilibrium.

These equations are found on the AP Physics 1 formula sheet. Understanding both GPE and spring potential energy is crucial for applying the principle of conservation of energy.

C. Conservation of Energy

Conservation of energy is a fundamental principle stating that the total energy of an isolated system remains constant. Energy can transform between kinetic energy (KE)‚ potential energy (PE) – both gravitational and spring – and other forms‚ but isn’t created or destroyed.

Mathematically‚ this is expressed as ΔE = KEf + PEf ⸺ KEi ⎯ PEi = 0. This principle‚ detailed on the AP Physics 1 formula sheet‚ allows solving problems involving work and energy without explicitly calculating work done by all forces.

Mastering this concept is vital for success on the AP exam‚ enabling efficient problem-solving in various scenarios.

V. Systems of Particles and Linear Momentum

Linear momentum (p)‚ defined as the product of mass (m) and velocity (v) – p = mv – is a crucial concept when analyzing systems of multiple particles. Understanding how momentum is conserved during collisions and interactions is key.

The center of mass represents the average position of all mass in a system‚ and its motion follows the same laws as a single particle. Impulse‚ the change in momentum‚ is equal to the force applied over a time interval.

Conservation of momentum dictates that the total momentum of an isolated system remains constant‚ a principle found on the AP Physics 1 formula sheet‚ essential for solving collision problems.

A. Center of Mass

The center of mass (COM) is a pivotal point representing the average position of all mass within a system. Calculating the COM involves summing the products of each particle’s mass and position‚ then dividing by the total mass – a formula readily available on the AP Physics 1 equation sheet.

Understanding the COM simplifies the analysis of complex systems; the system’s motion can be treated as if all its mass were concentrated at this single point. External forces act on the COM‚ dictating its acceleration.

For symmetrical objects‚ the COM often lies at the geometric center‚ but irregular shapes require careful calculation. Mastering COM is vital for analyzing collisions and rotational motion.

B. Impulse and Momentum

Momentum‚ the product of an object’s mass and velocity (p = mv)‚ is a crucial concept for understanding collisions and interactions. The AP Physics 1 equation sheet provides this fundamental formula.

Impulse‚ defined as the change in momentum‚ is caused by a force acting over a time interval (J = FΔt). It’s essential to recognize that impulse equals the change in momentum – a key principle for solving related problems.

During collisions‚ momentum is conserved in a closed system‚ meaning the total momentum before and after the collision remains constant. Understanding impulse and momentum is vital for analyzing real-world scenarios.

C. Conservation of Momentum

Conservation of momentum is a cornerstone principle in AP Physics 1‚ stating that the total momentum of a closed system remains constant if no external forces act upon it. This means momentum isn’t lost‚ only transferred.

In collisions – elastic or inelastic – momentum is always conserved. Elastic collisions also conserve kinetic energy‚ while inelastic collisions do not. The AP Physics 1 equation sheet doesn’t explicitly state conservation‚ but it’s implied through the momentum equation (p = mv).

Applying this principle involves setting the total momentum before an event equal to the total momentum after. Mastering this concept is crucial for solving collision problems and understanding interactions between objects.

VI. Rotation and Angular Momentum

Rotation and angular momentum extend the concepts of linear motion to circular paths. Key to understanding this is recognizing parallels between displacement‚ velocity‚ and acceleration‚ and their rotational counterparts: angular displacement‚ angular velocity‚ and angular acceleration.

The AP Physics 1 equation sheet provides essential formulas for rotational kinematics‚ torque‚ and rotational inertia. Torque‚ causing rotational acceleration‚ depends on force and the lever arm. Rotational inertia resists changes in rotational motion.

Angular momentum‚ a measure of an object’s rotating inertia‚ is conserved in a closed system‚ similar to linear momentum. Mastering these concepts is vital for analyzing rotating systems and their interactions.

A. Rotational Kinematics

Rotational kinematics describes the motion of objects rotating about an axis‚ mirroring linear kinematics. Instead of displacement‚ we have angular displacement (θ)‚ measured in radians. Angular velocity (ω) represents the rate of change of angular displacement‚ and angular acceleration (α) is the rate of change of angular velocity.

The AP Physics 1 equation sheet provides kinematic equations adapted for rotational motion. These equations‚ analogous to those for linear motion‚ relate angular displacement‚ initial angular velocity‚ angular acceleration‚ and time.

Understanding these equations allows you to solve problems involving rotating objects with constant angular acceleration‚ calculating quantities like final angular velocity and angular displacement. Remember to convert between radians and degrees when necessary!

B. Torque and Rotational Inertia

Torque (τ) is the rotational equivalent of force – it causes an object to rotate. It depends on the force applied and the lever arm (distance from the axis of rotation). The AP Physics 1 formula sheet will contain the equation τ = rFsinθ‚ where θ is the angle between the force and lever arm.

Rotational inertia (I)‚ also known as moment of inertia‚ is the resistance of an object to changes in its rotational motion‚ analogous to mass in linear motion. It depends on the object’s mass distribution relative to the axis of rotation.

Newton’s Second Law for rotation states τ = Iα‚ linking torque‚ rotational inertia‚ and angular acceleration. Mastering these concepts is crucial for analyzing rotational motion problems.

C. Angular Momentum and its Conservation

Angular momentum (L) is a measure of an object’s rotating inertia and is calculated as L = Iω‚ where I is the rotational inertia and ω is the angular velocity. It’s a vector quantity‚ with direction determined by the right-hand rule.

The AP Physics 1 formula sheet provides the tools to analyze systems where external torques are zero. In such cases‚ angular momentum is conserved – meaning the total angular momentum remains constant.

Understanding conservation of angular momentum is vital for problems involving spinning objects‚ like a figure skater pulling in their arms to increase rotation speed. This principle is fundamental to rotational dynamics.

VII. Simple Harmonic Motion

Simple Harmonic Motion (SHM) describes oscillatory motion where the restoring force is proportional to the displacement. Key characteristics include a sinusoidal pattern‚ defined by amplitude‚ period‚ and frequency.

The AP Physics 1 curriculum emphasizes understanding the relationship between these properties. The period (T) is the time for one complete oscillation‚ and frequency (f) is its inverse (f = 1/T).

Energy in SHM constantly interchanges between kinetic and potential forms. Total mechanical energy remains conserved‚ assuming no damping forces. Mastering these concepts‚ utilizing the AP formula sheet‚ is crucial for exam success.

A. Characteristics of SHM

Simple Harmonic Motion (SHM) is defined by its unique characteristics: restoring force‚ displacement‚ amplitude‚ period‚ and frequency. The restoring force is directly proportional to displacement‚ pulling the object back towards equilibrium.

Amplitude represents the maximum displacement from equilibrium‚ while the period (T) is the time for one complete oscillation. Frequency (f)‚ measured in Hertz‚ is the inverse of the period (f = 1/T).

Understanding these properties‚ and their relationships‚ is vital for solving AP Physics 1 problems. Utilize the equation sheet to recall formulas relating these characteristics‚ enabling accurate calculations and conceptual understanding of SHM.

B. Energy in SHM

Simple Harmonic Motion (SHM) involves a continuous exchange between kinetic energy (KE) and potential energy (PE). At maximum displacement (amplitude)‚ PE is maximized‚ and KE is zero. Conversely‚ at equilibrium‚ KE is maximized‚ and PE is zero.

Total mechanical energy (E) in SHM remains constant‚ assuming no non-conservative forces like friction. This energy is the sum of KE and PE: E = KE + PE. Understanding this energy conservation is crucial for AP Physics 1 problem-solving.

Refer to the AP Physics 1 equation sheet for formulas calculating KE and PE in SHM‚ allowing you to determine energy at any point in the oscillation and analyze system behavior.

VIII. Waves and Superposition

Waves transfer energy through a medium or space‚ characterized by frequency (f)‚ wavelength (λ)‚ and amplitude (A). The AP Physics 1 curriculum focuses on understanding these properties and their relationships‚ often utilizing the equation sheet for calculations.

Superposition occurs when two or more waves overlap. Interference is a result of superposition – constructive interference increases amplitude‚ while destructive interference decreases it. Mastering these concepts is vital for analyzing wave behavior.

Practice applying wave equations and understanding interference patterns. The AP exam frequently tests wave properties and superposition principles‚ so a strong foundation is essential for success.

A. Wave Properties (Frequency‚ Wavelength‚ Amplitude)

Wave properties are fundamental to understanding wave behavior in AP Physics 1. Frequency (f)‚ measured in Hertz (Hz)‚ represents the number of wave cycles per second. Wavelength (λ) is the distance between two successive crests or troughs‚ typically measured in meters.

Amplitude (A) defines the maximum displacement of a wave from its equilibrium position‚ influencing the wave’s energy. These properties are interconnected; the wave speed (v) is related by the equation v = fλ.

Utilize the AP Physics 1 equation sheet to practice calculations involving these properties. Understanding how changes in one property affect the others is crucial for solving exam problems effectively.

B. Superposition and Interference

Superposition describes the phenomenon where two or more waves overlap in the same space. The resulting displacement is the algebraic sum of the individual wave displacements. Interference occurs as a result of superposition‚ leading to constructive or destructive patterns.

Constructive interference happens when waves are in phase‚ resulting in an increased amplitude. Conversely‚ destructive interference occurs when waves are out of phase‚ leading to a decreased amplitude‚ potentially even cancellation.

Mastering these concepts requires utilizing the AP Physics 1 equation sheet and practicing problems involving wave interactions. Understanding phase differences is key to predicting interference patterns.

IX. The AP Physics 1 Equation Sheet

The AP Physics 1 Equation Sheet is an invaluable resource provided during the exam‚ containing essential formulas and constants. It’s crucial to familiarize yourself with its contents before test day‚ not to memorize it‚ but to understand how and when to apply each equation.

This sheet includes constants like gravitational acceleration (g) and conversion factors. It also lists equations for kinematics‚ dynamics‚ work‚ energy‚ momentum‚ and rotation. Knowing the sheet’s layout saves time during the exam.

Effective preparation involves practicing problems without the sheet initially‚ then using it to verify your approach and identify areas for improvement. Download the 2026 version for optimal practice!